The smell of memories:We learn differently, when it smells

RUB-researchers investigate memory

Our sense of smell influences how our brain stores information about novel objects. A particular part of the hippocampus plays an important role in this process.

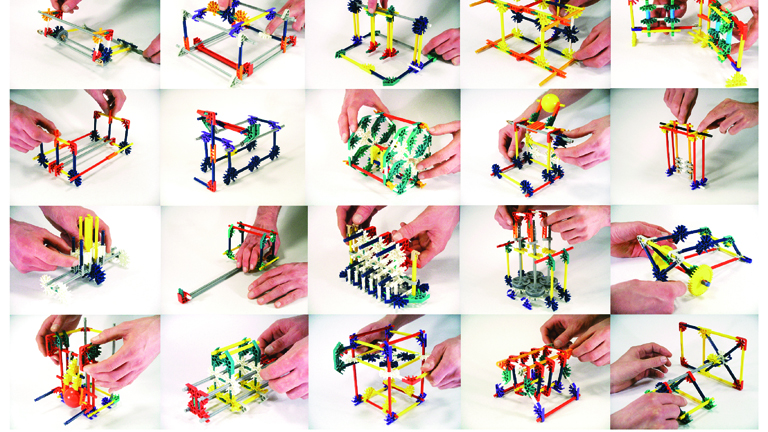

Building test objects from children’s toy

When we learn something new, we use all our senses to acquire information. Neuroscientists from the Ruhr University Bochum (RUB) and the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf have investigated how the brain stores these impressions. And they used a special method to do it.

Using a construction toy for children, they created novel objects, which were unknown to the study participants. By doing this, they were able to test how subjects perceived the items, without contaminating results with previous experience.

Little research on sense of smell

The team, led by Prof. Dr. Boris Suchan of the Department of Clinical Neuropsychology at the RUB and Prof. Dr. Christian Bellebaum of the Institute for Experimental Psychology at the Heinrich Heine University, were particularly interested in the sense of smell, since there has been little research in this field so far.

In the training phase the researchers showed the participants novel objects, while at the same time releasing a particular odour. For comparison, other objects were presented without odour. The participants were allowed to look at, but not touch the objects.

During a subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exam the participants were then shown pictures of objects and asked to decide whether they were known or unknown. The researchers then observed which areas of the brain were activated.

Hippocampus integrated different senses

“The analysis of the brain activity showed us that the right anterior hippocampus was more strongly activated, when objects were connected to a smell”, explains Suchan. The team reported on their findings in the journal “Behavioural Brain Research”.

As a hub for learning the hippocampus is engaged in many memory processes. The study shows that a particular part of this brain region becomes involved, when memories of smells are processed.

The scientists presume that this brain area integrates the information provided by different senses. Whether this is only true for sight and smell, or also for other senses, must now be investigated further.